Instead of substantive negotiations, instead of minimal care for the people who continue to die while the big bosses create chaos with the status of delegations and verbal duels, a history lesson a la Russe took place in Istanbul. Mr. Medinsky sprinkled the lesson with quotes from Napoleon and Bismarck, which, however, came not from history itself but from folk folklore, apparently Russian folk. The main point of this lesson was to justify the thesis that it is possible to simultaneously fight and negotiate a truce. In other words, calling things by their proper names, the purpose of the trip to Istanbul was to reject the absolutely sane and logical idea of "first a truce — then negotiations," and not the other way around. Was it worth going then if everything was clear in advance? In addition, the impression was spoiled by a leak according to which Medinsky spoke about Russia's readiness to fight for years.

Instead of substantive negotiations, instead of minimal care for the people who continue to die while the big bosses create chaos with the status of delegations and verbal duels, a history lesson a la Russe took place in Istanbul. Mr. Medinsky sprinkled the lesson with quotes from Napoleon and Bismarck, which, however, came not from history itself but from folk folklore, apparently Russian folk. The main point of this lesson was to justify the thesis that it is possible to simultaneously fight and negotiate a truce. In other words, calling things by their proper names, the purpose of the trip to Istanbul was to reject the absolutely sane and logical idea of "first a truce — then negotiations," and not the other way around. Was it worth going then if everything was clear in advance? In addition, the impression was spoiled by a leak according to which Medinsky spoke about Russia's readiness to fight for years.

The chief court historian reported that in principle, negotiations during wars are a common thing, practically the only way it is done. And among other things, he used the example of the Soviet-Finnish Winter War for illustration. Let's try to understand at least this one example.

The Finnish campaign of Stalin-Molotov, mournfully called by Alexander Tvardovsky the "uncelebrated war," which cost the Soviet Union enormous human losses, lasted three and a half months, not three plus years as it is now. The strategic significance of the conquered territory, as it turned out, was close to zero. The position of Leningrad did not become safer.

The Finns did not receive international assistance, or rather, they did, but only verbally from England and France, moreover, this assistance could provoke "unfriendly" actions by Germany against Finland. The Swedes limited themselves to sending volunteer units, and Swedish territory was closed to any transit. Even the initial failures of the much larger Red Army did not mean that Finland's defense would be successful. By February, a turning point in favor of Stalin had come, but he also realized the too high cost of the Finnish operation. Moreover, he seriously feared intervention by France and England, particularly possible bombings of Baku. Both sides were interested in ending the war and concluding a peace treaty with inevitable concessions from Finland.

The course of the negotiations, as well as discussions within the Finnish establishment, can be judged by the detailed memoirs of the chief negotiator from Finland, Juho Kusti Paasikivi. He was a very authoritative and very smart politician, the first Prime Minister of independent Finland, who spoke Russian and understood the intricate nature of the Russian soul, repeatedly met with Stalin and Molotov, and was completely devoid of any illusions about the maneuvers of both Stalinist and Western European diplomacy. He later became Finland's ambassador to the USSR in the period between the end of the Finnish War and the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, and in 1946 he was elected President of Finland.

Juho Kusti Paasikivi. Photo: YLE kuvapalvelu

It should be recalled that like Putin's campaigns, the Finnish War was initially assessed by Stalin as a "small victorious" one, in full accordance with the words of Lebedev-Kumach from the song by the Pokrass brothers in 1938: "And on enemy land, we will defeat the enemy / With little blood, with a mighty blow!" Bombings were present — there was a raid on Helsinki, a "mighty blow." But it did not go "with little blood," the operation turned into a bloody massacre. And it began with a classic provocation — a "false flag," as a response to artillery shelling from Finland, even though there was no Finnish artillery near the border at all.

The ideological support was similar to the propaganda clichés of 2022 — it was necessary to liberate the people from the yoke of a regime alien to them. On December 15, 1939, Stalin wrote to Otto Kuusinen, who was appointed head of the fake people's Finnish government:

«...I wish the Finnish people and the People's Government of Finland a quick and complete victory over the oppressors of the Finnish people, over the gang of Mannerheim-Tanner...»

As Ilf and Petrov said, "the same old dream!"

Stalin initially did not want negotiations because he hoped for military success. But they were too costly, and the intervention dragged on a bit. Contrary to expectations, the Finnish proletariat stood up to defend their homeland, rather than opening the "wide gates" to their class brothers, as sung in another propaganda song by the Pokrass brothers: the Sovietization of Finland was in question. So, as Trump would say, it was time to make a "deal."

The intermediary in the initial secret consultations was the writer Hella Wuolijoki, later convicted of collaborating with Soviet intelligence (operational pseudonym "Poet"). Contacts were made through the USSR's envoy in Stockholm, the legendary Alexandra Kollontai, who managed to be an outsider among her own, an insider among outsiders, but at the same time, for many years, did not lose at least relative trust from both sides. The secret exchange of mutual demands had been going on since the end of January 1940, and the channel worked flawlessly. Stalin's territorial claims seemed excessive to the Finns, but here Paasikivi himself proceeded from the fact that "the longer you delay negotiations, the harsher the conditions become."

The Finns had nowhere to expect help from, they knew nothing about the secret protocols, but they understood that they were in the sphere of division of interests of the "great powers," and for now, it made sense to talk with Stalin: Paasikivi had important insider information — Germany informed Sweden that it would consider direct assistance to Finland as a reason for war.

On March 8, 1940, Paasikivi, as the head of the official Finnish delegation, was already negotiating with Molotov, Zhdanov, whose mission as "governor-general" of Finland would later fail, and brigade commander Vasilevsky.

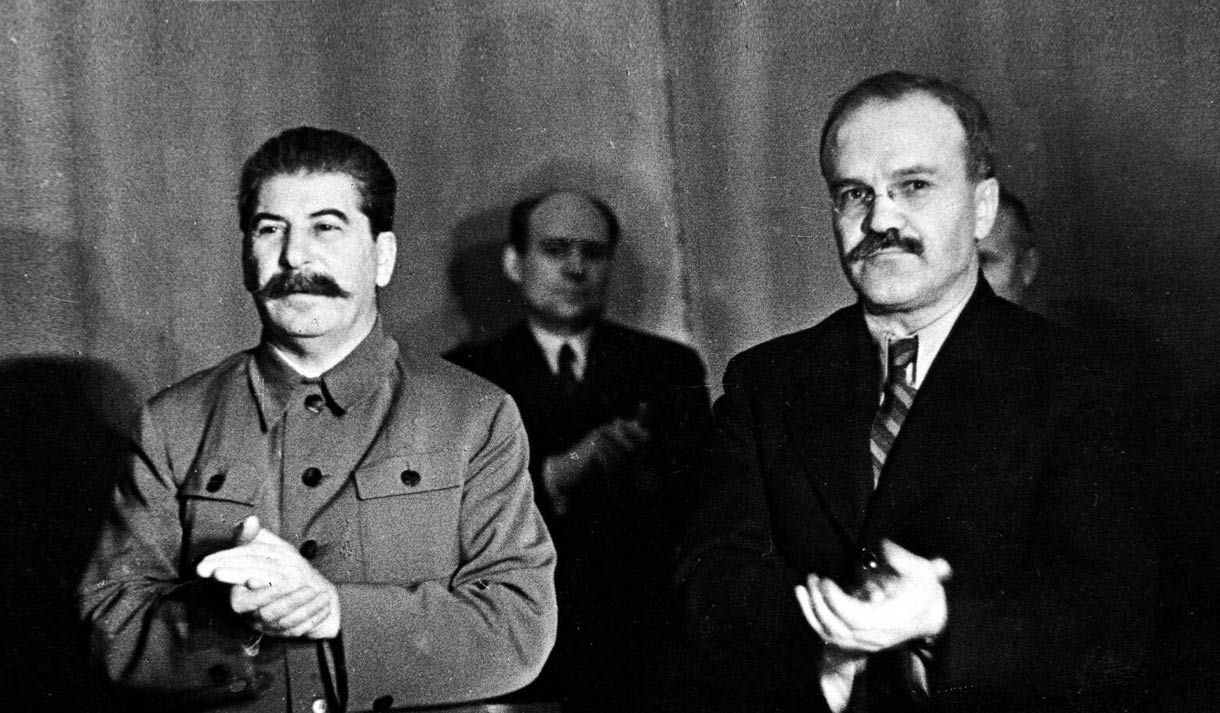

Stalin and Molotov, 1930s. Photo: historicus.media

And here begins another series of historical allusions to the present day. "Iron Ass" Molotov stated that the USSR "did not want war." But Finland, incited by, let's say in today's slang, "Westerners," and wanting to provide a platform on its territory for an attack on the Soviet Union, began military preparations: "This was not your own policy, but the result of foreign influence." That is, Finland's decision not to voluntarily give its territories to Stalin was not the demand of the Finns, but, speaking in today's Kremlin jargon, "sponsors," "curators," and "puppet masters."

Paasikivi had negotiated with the Soviet side before, but such a scale of straightforward lying was a shock even for him:

«...Listening to these accusations, we asked in amazement: did Molotov and Zhdanov themselves believe what they were saying? After all, it was not us who started the war, but the Soviet Union. This was noted by the League of Nations. But according to the Russians, this war seemed to be a war of England and France against Soviet Russia, which we allegedly unleashed in the fall of 1939 under the influence of Western powers...»

If at the beginning of the Winter War the Finns could still say, as in the Finnish song, "Njet, njet, Molotov", now it was Molotov's turn to say "no" to any proposals from the Finnish delegation to adjust Stalin's territorial claims. Moreover, and here one can see the similarity of Medinsky's, or rather Putin's, position with Molotov's negotiation tactics — Vyacheslav Mikhailovich refused a truce.

"First, we need to prepare the treaty," he said, "And only after that can military actions be stopped." On March 12, the Finnish delegation again attempted to raise the issue of a truce. The Prime Minister of Finland (soon to become President) Risto Ryti, participating in the negotiations, said:

«...To avoid unnecessary bloodshed, I propose to conclude a truce immediately, even before the ratification of the peace treaty. In my opinion, with the start of peace negotiations, there is no need to continue military actions and bloodshed...»

For Molotov, humanitarian, universal human logic was meaningless. The death of people: "Both the peace treaty and the truce will come into force simultaneously."

The peace treaty was signed on March 13 at one o'clock in the morning. At 11 o'clock in the morning, hostilities ceased. The conclusion of the Moscow Treaty was welcomed by the newspaper "Völkischer Beobachter":

«...Soviet Russia wanted nothing more than what was necessary for its security, the conditions of peace fairly satisfied the needs of a great power...»

The negotiations took six days. No one during this time intended to return to Finland. The exchange of information between the delegation and Helsinki was carried out using such a tool of modern civilization as telegrams.

In short, the similarity with today's situation is not that hostilities allegedly always continue during negotiations (six days is not weeks, months, and years), but in the logic of the Soviet negotiating side, not ready to consider human losses. As Paasikivi accurately noted, the opposite side had "different moral values."

According to official data, Soviet losses in manpower amounted to 126,875 people, that is, as historian Kimmo Rentola notes, "in 105 days of war much more than in ten years in Afghanistan."

P. S.

«...We need to kill all the rest, then the matter will end, — Stalin optimistically stated on January 21, 1940 (according to Georgy Dimitrov's notes) about the population of Finland. — We need to leave only children and old people. We do not want the territory of Finland. The only thing required from Finland is that it becomes a friendly power to the Soviet Union...»

Stalin did not get any of this, except for fragments of territories. And Finland became a friendly power under Khrushchev. It remained so for decades and in the post-Soviet years. Until Putin's special military operation.

* Andrey Kolesnikov is considered a "foreign agent" by the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation.